What Was The Runaway Scrape

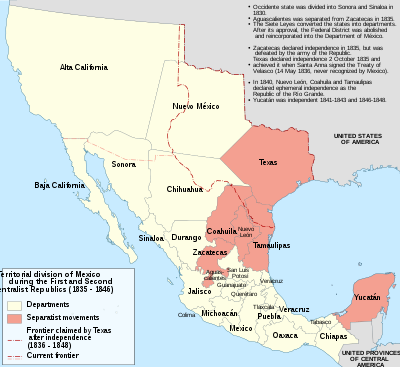

A map of Mexico, 1835–46, showing administrative divisions.

The Runaway Scrape events took place mainly betwixt September 1835 and Apr 1836 and were the evacuations past Texas residents fleeing the Mexican Army of Operations during the Texas Revolution, from the Battle of the Alamo through the decisive Battle of San Jacinto. The ad interim government of the new Republic of Texas and much of the civilian population fled eastward ahead of the Mexican forces. The disharmonize arose after Antonio López de Santa Anna abrogated the 1824 Constitution of Mexico and established martial constabulary in Coahuila y Tejas. The Texians resisted and declared their independence. Information technology was Sam Houston'south responsibility, as the appointed commander-in-chief of the Provisional Regular army of Texas (before such an army actually existed), to recruit and train a military machine strength to defend the population against troops led by Santa Anna.

Residents on the Gulf Coast and at San Antonio de Béxar began evacuating in January upon learning of the Mexican army's troop movements into their area, an outcome that was ultimately replayed across Texas. During early skirmishes, some Texian soldiers surrendered, believing that they would become prisoners of state of war — but Santa Anna demanded their executions. The news of the Battle of the Alamo and the Goliad massacre instilled fear in the population and resulted in the mass exodus of the civilian population of Gonzales, where the opening battle of the Texian revolution had begun and where, only days before the fall of the Alamo, they had sent a militia to reinforce the defenders at the mission. The noncombatant refugees were accompanied by the newly forming provisional army, equally Houston bought time to train soldiers and create a war machine structure that could oppose Santa Anna's greater forces. Houston's actions were viewed equally cowardice past the ad interim government, likewise as past some of his ain troops. As he and the refugees from Gonzales escaped starting time to the Colorado River and then to the Brazos, evacuees from other areas trickled in and new militia groups arrived to join with Houston'due south strength.

The towns of Gonzales and San Felipe de Austin were burned to keep them out of the easily of the Mexican army. Santa Anna was intent on executing members of the Republic'southward interim government, who fled from Washington-on-the-Brazos to Groce'south Landing to Harrisburgh and New Washington. The regime officials eventually escaped to Galveston Island, and Santa Anna burned the towns of Harrisburgh and New Washington when he failed to find them. Approximately v,000 terrified residents of New Washington fled from the Mexican regular army. After a little over a month of training the troops, Houston reached a crossroads where he ordered some of them to escort the fleeing refugees farther east while he took the primary ground forces southeast to engage the Mexican regular army. The subsequent Battle of San Jacinto resulted in the surrender of Santa Anna and the signing of the Treaties of Velasco.

Prelude [edit]

Changes in Mexico: 1834 – 1835 [edit]

In 1834, Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna shifted from a federalist political ideology to creating a centralist government and revoked the country's constitution of 1824.[FN 1] That constitution had established Coahuila y Tejas[FN 2] as a new Mexican country and had provided for each land in Mexico to create its own local-level constitution.[three] After eliminating land-level governments, Santa Anna had in effect created a dictatorship, and he put Coahuila y Tejas under the war machine dominion of General Martín Perfecto de Cos.[4] When Santa Anna fabricated Miguel Barragán temporary president, he also had Barragán install him as caput of the Mexican Ground forces of Operations.[5] Intending to put down all rebellion in Coahuila y Tejas, he began amassing his army on Nov 28, 1835, [6] soon followed by General Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma leading the Vanguard of the Advance across the Rio Grande in December.[7]

Temporary governments in Texas: November 1835 – March 1836 [edit]

Sam Houston army recruitment annunciation December 12, 1835

Stephen F. Austin was commander of the existing unpaid volunteer Texian army, and at his urging[eight] the Consultation of 1835 convened in San Felipe de Austin on Nov 3 of that year. Their cosmos of a provisional government based on the 1824 constitution[9] established the General Council as a legislative body with each municipality allotted one representative.[10] Henry Smith was elected governor without whatsoever clearly defined powers of the position.[11] Sam Houston was in attendance as the elected representative from Nacogdoches, who also served as commander of the Nacogdoches militia.[12] Edward Burleson replaced Austin as commander of the volunteer army on December 1.

On December 10, the General Council chosen new elections to choose delegates to determine the fate of the region.[xiii] The Consultation approved the creation of the Provisional Army of Texas, a paid strength of 2,500 troops. Houston was named commander-in-chief of the new army and issued a recruitment proclamation on December 12.[FN 3] [FN four] The volunteer regular army under Burleson disbanded on December twenty.[16]

Harrisburgh was designated the seat of a securely divided provisional government on December xxx.[17] About of the Full general Council wanted to remain office of Mexico, but with the restoration of the 1824 constitution. Governor Smith supported the opposing faction who advocated for consummate independence. Smith dissolved the Full general Council on January 10, 1836, but information technology was unclear if he had the ability to do that. He was impeached on January 11. The power struggle finer shut down the government.[18]

The Convention of 1836 met at Washington-on-the-Brazos on March 1.[19] The following day, the 59 delegates created the Republic of Texas by affixing their signatures to the Texas Announcement of Independence.[20] Houston's military dominance was expanded on March four to include "the country forces of the Texian army both Regular, Volunteer, and Militia."[21] The delegates elected the Democracy's ad interim government on March 16,[22] with David Chiliad. Burnet as president, Lorenzo de Zavala as vice president, Samuel P. Carson as secretarial assistant of state, Thomas Jefferson Rusk equally secretarial assistant of war, Bailey Hardeman as secretary of the treasury, Robert Potter as secretary of the navy, and David Thomas equally attorney full general.[23]

Battle of Gonzales: October 2, 1835 [edit]

Boxing of Gonzales cannon

The Battle of Gonzales was the onset of a concatenation of events that led to what is known as the Runaway Scrape. The confrontation began in September 1835, when the Mexican regime attempted to reclaim a statuary cannon that it had provided to Gonzales in 1831 to protect the town against Indian attacks. The offset attempt past Corporal Casimiro De León resulted in De León'due south disengagement being taken prisoners, and the cannon existence buried in a peach orchard.[24] James C. Neill, a veteran who had served at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend nether Andrew Jackson, was put in charge of the artillery after it was later dug upwardly and wheel mounted.[25] When Lieutenant Francisco de Castañeda arrived accompanied by 100 soldiers and made a second attempt at repossessing the cannon, Texians dared the Mexicans to "come and accept it".[24] John Henry Moore led 150 Texian militia on October 2 in successfully repelling the Mexican troops. A "Come and Take It" flag was afterward fashioned by the women of Gonzales.[26] The cannon was moved to San Antonio de Béxar and became one of the arms pieces used by the defenders of the Alamo.[FN v]

The immediate consequence of the Texian victory at Gonzales was that ii days later the number of volunteers had swelled to over 300, and they were adamant to drive the Mexican army out of Texas.[28] Simultaneously, a company of volunteers under George M. Collinsworth captured the Presidio La Bahía from the Mexicans on October 9 at the Battle of Goliad.[29] The Mexican government's response to the unrest in Texas was an Oct xxx authority of state of war.[30] On the banks of the Nueces River three miles (iv.eight km) from San Patricio on November 4 during the Battle of Lipantitlán, volunteers nether Ira Westover captured the fort from Mexican troops.[31]

Béxar: 1835–1836 [edit]

Siege of Béxar and its backwash: October 1835 – February 1836 [edit]

By October 9, Cos had taken over San Antonio de Béxar.[xxx] Stephen F. Austin sent an advance picket troop of xc men under James Bowie and James Fannin to observe the Mexican forces. While taking refuge at Mission Concepción on Oct 28, they repelled an attack by 275 Mexicans under Domingo Ugartechea.[32] Austin continued to ship troops to Béxar. Bowie was ordered on November 26 to attack a Mexican supply train allegedly conveying a payroll. The resulting skirmish became known every bit the Grass Fight, subsequently it was discovered that the just cargo was grass to feed the horses.[33] When Austin was selected to bring together Branch T. Archer and William H. Wharton on a diplomatic mission to seek international recognition and back up, Edward Burleson was named every bit commander.[34] On December five, James C. Neill began distracting Cos by firing arms directly at the Alamo, while Benjamin Milam and Frank W. Johnson led several hundred volunteers in a surprise attack. The fighting at the siege of Béxar continued until Dec 9 when Cos sent word he wanted to give up. Cos and his men were sent back to Mexico but later united with Santa Anna's forces.[35]

Approximately 300 of the Texian garrison at Béxar departed on Dec 30 to join Johnson and James Grant on the Matamoros Trek, in a planned attack to seize the port for its financial resources.[36] Proponents of this campaign were hoping Mexican Federalists[FN 1] would oust Santa Anna and restore the 1824 constitution.[37] When Sesma crossed the Rio Grande, residents of the Gulf Coast began fleeing the area in Jan 1836.[38] On February 16, Santa Anna ordered Full general José de Urrea to secure the Gulf Coast.[39] Virtually 160 miles (260 km) north of Matamoros at San Patricio, Urrea's troops ambushed Johnson and members of the expedition on February 27 at the Battle of San Patricio. In the skirmish, xvi Texians were killed, 6 escaped, and 21 were taken prisoner.[xl] Urrea's troops and then turned southwest by some 26 miles (42 km) to Agua Dulce Creek and on March ii attacked a group of the expedition led by Grant, killing all but eleven, six of whom were taken prisoner. Five of the men escaped the Battle of Agua Dulce and joined Fannin who wanted to increase the defense force forcefulness at Goliad.[41]

The Alamo: Feb 1836 [edit]

Neill was promoted to lieutenant colonel during his participation in the siege of Béxar,[25] and ten days later Houston placed him in charge of the Texian garrison in the city.[42] In January residents had begun evacuating ahead of Santa Anna's budgeted forces.[43] Neill pleaded with Houston for replenishment of troops, supplies and weaponry. The departure of Texians who joined the Matamoros Trek had left Neill with but nearly 100 men. At that point Houston viewed Béxar as a military machine liability and did non desire Santa Anna'due south advancing ground forces gaining command of any remaining soldiers or arms. He dispatched Bowie with instructions to remove the artillery, accept the defenders abandon the Alamo mission and destroy information technology.[FN 6] Upon his January xix inflow[18] and subsequent discussions with Neill, Bowie decided the mission was the correct identify to stop the Mexican army in its tracks. He stayed and began to help Neill prepare for the coming attack. Lieutenant Colonel William B. Travis arrived with reinforcements on February three.[45] When Neill was given get out to nourish to family matters on Feb 11, Travis assumed command of the mission, and 3 days after he and Bowie agreed to a joint command.[46] Santa Anna crossed the Rio Grande on February 16, and the Mexican army's assault on the Alamo began Feb 23.[39] Captain Juan Seguín left the mission on February 25, carrying a letter from Travis to Fannin at Goliad requesting more than reinforcements.[47] Santa Anna extended an offer of immunity to Tejanos inside the fortress; a non-combatant survivor, Enrique Esparza, said that most Tejanos left when Bowie brash them to have the offer.[48] In response to Travis' February 24 alphabetic character To the People of Texas, 32 militia volunteers formed the Gonzales Ranging Company of Mounted Volunteers and arrived at the Alamo on Feb 29.[FN 4]

If you execute your enemies, it saves yous the trouble of having to forgive them.

—General Antonio López de Santa Anna, Feb 1836[49]

Fall of the Alamo, and the runaway flight: March – April 1836 [edit]

Houston begins forming his army [edit]

Every bit the closest settlement to San Antonio de Béxar, Gonzales was the rallying point for volunteers who responded to both the Travis alphabetic character from the Alamo and Houston's recruitment pleas. Recently formed groups came from Austin and Washington counties and from the Colorado River area.[fifty] Volunteers from Brazoria, Fort Bend and Matagorda counties organized after arriving in Gonzales.[51] The Kentucky Rifle company under Newport, Kentucky, business human being Sidney Sherman had been aided by funding from Cincinnati, Ohio, residents.[52]

Alamo commandant Neill was in Gonzales purchasing supplies and recruiting reinforcements on March six, unaware that the Alamo had fallen to Mexican forces that morning time. When Seguin learned en road that Fannin would be unable to reach the Alamo in time,[53] he immediately began mustering an all-Tejano company of scouts.[54] His men combined with Lieutenant William Smith's and volunteered to accompany Neill's recruits. They encountered the Mexican army 18 miles (29 km) from the Alamo on March 7, and Neill's men turned back while the Seguin-Smith scouts moved forwards.[55] Every bit the scouts neared the Alamo, they heard only silence.[56] Andrew Barcena and Anselmo Bergara from Seguin's other detachment inside the Alamo showed up in Gonzales on March 11, telling of their escape and delivering news of the March half-dozen slaughter. Their stories were discounted; Houston, who had arrived that same mean solar day, denounced them every bit Mexican spies.[57]

Smith and Seguin confirmed the fate of the Alamo upon their render. Houston dispatched orders to Fannin to abandon Goliad, blow up the Presidio La Bahía fortress, and retreat to Victoria,[58] but Fannin delayed interim on those orders. Believing the approach of Urrea'south troops brought a greater urgency to local civilians, he sent 29 men under Captain Amon B. King to help evacuate nearby Refugio.[59]

Houston promptly began organizing the troops at Gonzales into the First Regiment under Burleson who had arrived as part of the Mina volunteers.[60] A second regiment would later exist formed when the army grew large plenty.[61] As others began to arrive, individual volunteers not already in another company were put nether Captain William Hestor Patton.[62] Houston had 374 volunteers and their commanders in Gonzales on March 12.[63]

Santa Anna sent Susanna Dickinson with her infant daughter Angelina, Travis' slave Joe, and Mexican Colonel Juan Almonte's cook Ben to Gonzales, with dispatches written in English past Almonte to spread the news of the fall of the Alamo.[64] Scouts Deaf Smith, Henry Karnes and Robert Eden Handy encountered the survivors xx miles (32 km) outside of Gonzales on March 13. When Karnes returned with the news, 25 volunteers deserted. Wailing filled the air when Dickinson and the others reached the town with their starting time-hand accounts.[38]

There was not a soul left amongst the citizens of Gonzales who had not lost a father, hubby, brother or son ... That terrible massacre had, for a time, struck terror into every center.

—John Milton Swisher, private in William Westward. Hill's volunteers.[65]

The Sam Houston Oak[FN seven] where the Provisional Regular army of Texas rested afterward the burning of Gonzales

Although noncombatant evacuations had begun in Jan for the Gulf Declension and San Antonio de Béxar, the Texian military was either on the offensive or standing firm until the smaller Gulf Coast skirmishes happened in February. Houston was now facing a choice of whether to retreat to a safe place to railroad train his new ground forces, or to meet the enemy caput-on immediately.[66] He was wary of trying to defend a stock-still position – the debacle at the Alamo had shown that the new Texian regime was unable to provide sufficient provisions or reinforcements.[67]

Called-for of Gonzales [edit]

Houston chosen for a council of state of war. The officers voted that the families should exist ordered to go out, and the troops would cover the retreat. By midnight, less than an 60 minutes after Dickinson had arrived, the combined ground forces and noncombatant population began a frantic movement eastward,[66] leaving backside everything they could not immediately take hold of and transport. Much of the provisions and artillery were left backside, including two 24-pounder cannon.[68] Houston ordered Salvador Flores along with a company of Juan Seguin's men to class the rear guard to protect the fleeing families. Couriers were sent to other towns in Texas to warn that the Mexican army was advancing.[69]

The retreat took place and so chop-chop that many of the Texian scouts did not fully cover it until afterward the town was evacuated.[seventy] Houston ordered Karnes to burn the town and everything in it so goose egg would remain to benefit the Mexican troops. By dawn, the unabridged town was in ashes or flames.[71]

Volunteers from San Felipe de Austin who had been organized nether Captain John Bird on March 5 to reinforce the men at the Alamo[72] had been en route to San Antonio de Béxar on March 13 when approximately ten miles (xvi km) east of Gonzales they encountered fleeing citizens and a courier from Sam Houston. Told of the Alamo'south fall, Bird's men offered assistance to the fleeing citizens and joined Houston'south regular army at Bartholomew D. McClure'southward plantation on the evening of March 14.[FN 7]

At Washington-on-the-Brazos, the delegates to the convention learned of the Alamo'south fall on March 13.[74] The Republic'due south new advertisement interim government was sworn in on March 17, with a section overseeing military spy operations, and adjourned the same day.[75] The regime and so fled to Groce'due south Landing where they stayed for several days before moving on to Harrisburgh on March 21, where they established temporary headquarters in the home of widow Jane Birdsall Harris.[76]

Male monarch's men at Refugio had taken refuge in Mission Nuestra Señora de la Rosario when they were subsequently attacked by Urrea's forces. Fannin sent 120 reinforcements under William Ward, simply the March fourteen Battle of Refugio cost 15 Texian lives.[77] Ward's men escaped, merely King's men were captured and executed on March 16.[78]

Colorado River crossings [edit]

Upon learning of the flight, Santa Anna sent General Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma with 700 men to pursue Houston, and 600 men under General Eugenio Tolsa as reinforcements. Finding just burned remains at Gonzales, Sesma marched his ground forces toward the Colorado River.[79]

The Texian army camped March fifteen–eighteen on the Lavaca River belongings of Williamson Daniels[80] where they were joined by combined forces nether Joe Bennett and Captain Peyton R. Splane.[81] Fleeing civilians accompanied Houston'due south regular army turning due north at the Navidad River as they crossed to the e side of the Colorado River at Burnam's Crossing.[82] The ferry and trading post, also as the family unit dwelling house of Jesse Burnam, were all burned at Houston's orders on March 17 to prevent Santa Anna'southward army from making the same crossing.[FN 8]

Campaigns of the Texas Revolution

Beason'south Crossing was located where Columbus is today.[84] DeWees Crossing was 7 miles (11 km) north of Beason's. From March 19 through March 26, Houston split his forces between the 2 crossings.[85] Additional Texian volunteer companies began arriving at both crossings, including 3 companies of Texas Rangers, the Freedom County Volunteers and the Nacogdoches Volunteers.[86]

Sesma's battalion of approximately 725 men and artillery camped on the opposite side of the Colorado, at a altitude halfway between the two Texian camps.[87] To prevent Sesma'south troops from using William DeWees' log cabin, Sherman ordered information technology burned.[88] 3 Mexican scouts from Sesma'south army were captured by Sherman's men, and although Sherman argued for an attack on Sesma's troops, Houston was not ready.[89]

Fannin had begun evacuating Presidio La Bahía on March nineteen. The estimated 320 troops were low on food and water, and the breakdown of a carriage allowed Urrea'south men to overtake them at Coleto Creek, ending in Fannin'south give up on March 20.[90] Peter Kerr, who had served with Fannin and claimed to have been held prisoner, arrived at DeWees Crossing on March 25. Houston announced Fannin's surrender[91] but would later merits to have uncovered evidence that Kerr was a spy for the Mexicans.[92]

The Texian army was a force of 810 volunteers and staff at this point,[93] but few had any military training and experience. Faced with past desertions, bailiwick flaws, and individual indecisiveness of volunteers in grooming, Houston knew they were not yet ready to engage the Mexican army. Compounding the state of affairs were the civilian refugees dependent upon the army for their protection.[94] The news of Fannin's capture, combined with his doubts about the readiness of the Texian regular army, led Houston to order a retreat on March 26.[95] Some of the troops viewed the determination every bit cowardice with Sesma sitting just on the other side of the Colorado, and several hundred men deserted.[96]

... the only ground forces in Texas is now present ... There are but few of us, and if we are beaten, the fate of Texas is sealed. The salvation of the country depends upon the first battle had with the enemy. For this reason, I intend to retreat, if I am obliged to get even to the banks of the Sabine.

—Sam Houston[97]

Brazos River training camp [edit]

Groce's Landing [edit]

Texian survivors of the Battle of Coleto Creek believed their surrender agreement with Urrea would, at worst, mean their deportation. Santa Anna, even so, adhered to the 1835 Tornel Prescript that stated the insurrection was an human activity of piracy fomented by the Usa and ordered their executions.[FN ix] Although he personally disagreed with the need to practice and so, Urrea carried out his commander'due south orders on March 27.[99] Of the estimated 370 Texians being held, a few managed to escape the massacre at Goliad. The residuum were shot, stabbed with bayonets and lances and clubbed with gun butts. Fannin was shot through the confront and his gold lookout stolen. The expressionless were cremated on a pyre.[100]

The retreating Texian army stopped at San Felipe de Austin[101] on March 28–29 to stock up on food and supplies.[102] Houston'southward plan to move the army north to Groce'southward Landing on the Brazos River was met with resistance from captains Wyly Martin and Moseley Baker, whose units balked at further retreat. Houston reassigned Martin 25 miles (40 km) south to protect the Morton Ferry crossing at Fort Bend, and Bakery was ordered to guard the river crossing at San Felipe de Austin.[103]

News of approaching Mexican troops and Houston's retreat caused panic among the population in the counties of Washington, Sabine, Shelby and San Augustine. Among the confusion of fleeing residents of those counties, 2 volunteer groups under captains William Kimbro and Benjamin Bryant arrived to bring together Houston on March 29. Kimbro was ordered to San Felipe de Austin to reinforce Baker's troops, while Bryant's men remained with the master army.[104]

Subsequently an erroneous scouting written report of approaching Mexican troops, Baker burned San Felipe de Austin to the basis on March 30.[105] When Baker claimed Houston had given him an order to do and so, Houston denied it.[106] Houston'due south account was that the residents burned their own holding to go on it out of the hands of the Mexican ground forces.[91] San Felipe de Austin'southward residents fled to the east.[105]

During a two-week menstruation beginning March 31, the Texian army camped on the west side of the Brazos River in Austin County, near Groce's Landing (besides known equally Groce'southward Ferry).[107] Every bit Houston led his army n towards the landing, the unrelenting rainy weather condition swelled the Brazos and threatened flooding.[108] Groce'due south Landing was transformed into a training camp for the troops.[109] Major Edwin Morehouse arrived with a New York battalion of recruits who were immediately assigned to aid Wyly Martin at Fort Bend.[110] Civilian men who were fleeing the Mexicans enlisted,[111] and displaced noncombatant women in the campsite helped the army's efforts past sewing shirts for the soldiers.[112]

Samuel M. Hardaway, a survivor of Major William Ward's group who had escaped the Battle of Refugio and re-joined Fannin at the Battle of Coleto, also managed to escape the Goliad massacre. As he fled Goliad, he was eventually joined by 3 other survivors, Joseph Andrews, James P. Trezevant and M. K. Moses. Spies for the Texian ground forces discovered the 4 men and took them to Baker's camp virtually San Felipe de Austin on April 2.[113] Several other survivors of the Goliad massacre were plant on April 10 past Texian spies. Survivors Daniel White potato, Thomas Kemp, Charles Shain, David Jones, William Brenan and Nat Hazen were taken to Houston at Groce's Landing where they enlisted to fight with Houston'south regular army.[114]

Houston learned of the Goliad massacre on April iii. Unaware that Secretarial assistant of War Rusk was already en route to Groce's Landing with orders from President Burnet to halt the army'due south retreat and appoint the enemy, he relayed the Goliad news by letter to Rusk.[115]

The enemy are laughing y'all to contemptuousness. Yous must fight them. You must retreat no further. The country expects you to fight. The salvation of the land depends on your doing and then.

—David G. Burnet, ad interim president of the Republic of Texas[116]

Empowered to remove Houston from control and take over the army himself, Rusk instead assessed Houston's program of action as correct, later witnessing the training taking place at Groce's Landing. Rusk and Houston formed the Second Regiment on Apr 8 to serve nether Sherman, with Burleson retaining command of the First Regiment.[FN 10]

Yellowstone steamboat [edit]

The steamboat Yellowstone [112] under the control of Captain John Eautaw Ross was impressed into service for the Provisional Army of Texas on April ii and initially ferried patients beyond the Brazos River when Dr. James Aeneas Phelps established a field infirmary at Bernardo Plantation.[118] Iii days afterwards, Santa Anna joined with Sesma'southward troops[119] and had them build flatboats to cantankerous the Brazos as the Mexicans sought to overtake and defeat the Texians.[120] Wyly Martin reported on April eight that Mexican forces had divided and were headed both east to Nacogdoches and southeast to Matagorda.[121] Houston reinforced Baker's post at San Felipe de Austin on April 9,[122] as Santa Anna continued moving southeast on April ten.[123]

The Texian army was transported by the Yellowstone over to the east side of the Brazos on April 12, where they set up camp at the Bernardo Plantation.[124] Afterwards walking 50 miles (80 km) from Harrisburgh, Mirabeau B. Lamar arrived at Bernardo to enlist every bit a private in Houston'southward army and suggested using the steamer for guerilla warfare.[125]

Had information technology not been for its service, the enemy could never have been overtaken until they had reached the Sabine ... utilise of the gunkhole enabled me to cross the Brazos and save Texas.

—Sam Houston on the Yellowstone's contributions[126]

With Bakery guarding the crossing at San Felipe de Austin, and Martin guarding the Morton Ferry crossing[127] at Ford Bend, Santa Anna opted on Apr 12 to cantankerous the Brazos halfway between at Thompson'due south Ferry,[128] with Sesma'due south men and artillery crossing over the next day.[129] The Mexican ground forces attacked the steamer numerous times in an effort to capture it, but Ross successfully used cotton bales to protect the steamer and its cargo and was able to go on the Yellowstone away from Mexican control.[129] Houston released the steamboat from service on April 14, and information technology sailed on to Galveston.[130]

Burning of Harrisburgh and the crucial crossroads [edit]

The advertizing interim government departed Harrisburgh on the steamboat Cayuga for New Washington ahead of Santa Anna's April fifteen arrival,[131] thwarting his plans to eliminate the unabridged regime of the Republic of Texas.[132] Three printers still at work on the Telegraph and Texas Annals told the Mexican army that anybody in the regime had already left, and Santa Anna responded by having the printers arrested and the printing presses tossed into Buffalo Bayou.[133] Subsequently days of looting and seeking out information about the government, Santa Anna ordered the boondocks burned on April 18.[134] He later tried to identify the arraign for the devastation on Houston.[135]

Before the Texian army left Bernardo Plantation, they welcomed the arrival of two cannon cast in Cincinnati, Ohio, funded entirely by the people of that urban center equally a donation to the Texas Revolution. The idea had arisen as a suggestion from Robert F. Lytle, one of the businessmen who helped fund Sherman's Kentucky Riflemen.[136] Arriving in New Orleans after a lengthy trip from Ohio on the Mississippi River, the cannon were transported to the Gulf Coast aboard the Pennsylvania schooner. The cannons were nicknamed the "Twin Sisters", perhaps in award of the twins Elizabeth and Eleanor Rice traveling aboard the Pennsylvania, who were to present the cannon upon their arrival at Galveston in April 1836.[137] [138] At Galveston, Leander Smith had the responsibleness of transporting the cannon from Harrisburgh to Bernardo Plantation. Along the mode, Smith recruited 35 men into the army.[139] Lieutenant Colonel James Neill was put in charge of the cannon once they arrived in camp.[140]

Martin and Baker abandoned the river crossings on Apr 14 and re-joined Houston'south army which had marched from Bernardo to the Charles Donoho Plantation most present-mean solar day Hempstead in Waller County.[141] Every bit news spread of the Mexican army'southward movements, residents of Nacogdoches and San Augustine began to flee eastward towards the Sabine River. Afterwards refusals to proceed with the army, Martin was ordered past Houston to accompany displaced families on their flight due east. Hundreds of soldiers left the ground forces to help their families. The primary ground forces parted from the refugees at this indicate, and interim Secretary of State of war David Thomas[FN x] advised Houston to move southward to secure Galveston Bay.[142] Houston, yet, was getting conflicting advice from the chiffonier members. President Burnet had sent Secretary of Country Carson to Louisiana in hopes of getting the United States regular army and private state militias involved in the Texas fight for independence. While he attempted to secure such involvement, Carson sent a dispatch to Houston on April 14 advising him to retreat all the fashion to the Louisiana-Texas border on the Sabine River and bide his fourth dimension before engaging the Mexican army.[143]

The Texian army camped west of present-mean solar day Tomball on April 15, at Sam McCarley's homestead.[144] They departed the next morning[145] and 3 miles (4.8 km) due east reached a crucial crossroads.[FN 11] I route led east to Nacogdoches and eventually the Sabine River and Louisiana, while the other route led southeast to Harrisburgh. The army was concerned that Houston would continue the eastward retreat. Although Houston discussed his conclusion with no i, he led the army down the southeast road. Rusk ordered that a small group of volunteers be split from the army to secure Robbins'south Ferry on the Trinity River.[147] Houston's troops stopped overnight on April xvi at the home of Matthew Burnet and the next forenoon connected marching towards Harrisburgh, 25 miles (xl km) southeast.[148]

With the refugee families being accorded a armed forces escort eastward and Houston marching southeast, the retreat of the Provisional Ground forces of Texas was over. On the march which would lead to San Jacinto, moving the heavy artillery across rain-soaked terrain slowed the ground forces'southward progress.[140] The regular army had previously been assisted in moving the Twin Sisters with oxen borrowed from refugee Pamela Mann when she believed the army was fleeing towards Nacogdoches. When she learned the army was headed towards Harrisburgh and a confrontation with the Mexican ground forces, she reclaimed her oxen.[149] The Texian ground forces had expanded to 26 companies past the time they reached Harrisburgh on April 18 and saw the destruction Santa Anna had left behind.[150] [151]

New Washington [edit]

On orders of Santa Anna after the burning of Harrisburgh, Almonte went in pursuit of the advertisement interim government at New Washington. During their flying the Republic officials switched from steamer to ferry to skiff. On the last leg of the trip, Almonte finally had them in his sights but refused to fire after he saw Mrs. Burnet and her children on the skiff.[152] In addition to letting the government get away 1 more time, Almonte's spies had misread Houston'south troop movements, and Santa Anna was told that the Texian army was all the same retreating eastward, this time through Lynchburg.[153]

New Washington was looted and burned on Apr xx by Mexican troops,[154] and equally many as v,000 civilians fled, either by boat or beyond land. Those attempting to cross the San Jacinto River were bottlenecked for three days, and the vicinity effectually the crossing transformed into a refugee camp. Burnet ordered government assist all beyond Texas for fleeing families.[155]

Battle of San Jacinto [edit]

In a troop movement that took all night on a makeshift raft, the Texian regular army crossed Buffalo Bayou at Lynchburg April xix with 930 soldiers, leaving backside 255 others as guards or for reasons of illness.[156] It was suggested that Twin Sisters be left behind every bit protection, merely Neill was adamant that the cannons be taken into the battle.[157] In an April 20 skirmish, Neill was severely wounded,[158] and George Hockley took command of the heavy artillery.[159] Estimates of the Mexican regular army troop force on the day of the main battle range from 1,250 to ane,500.[160]

The Texians attacked in the afternoon of April 21 while Santa Anna was even so under the misconception that Houston was really retreating.[161] He had allowed his army time to relax and feed their horses, while he took a nap.[162] When he was awakened by the assail, he immediately fled on horseback merely was later captured when Sergeant James Austin Sylvester plant him hiding in the grass.[163] Houston'southward own business relationship was that the boxing lasted "about eighteen minutes",[161] earlier apprehending prisoners and confiscating armaments.[164] When the Twin Sisters went up against the Mexican army'due south Golden Standard cannon, they performed and so well that Hockley's unit was able to capture the Mexican cannon.[FN 12]

Aftermath [edit]

The Yellowstone saw state of war service for the Republic one more fourth dimension on May 7, when information technology transported Houston and his prisoner Santa Anna, along with the authorities Santa Anna tried to extinguish, to Galveston Isle.[FN 13] From there, the government and Santa Anna traveled to Velasco for the signing of treaties.[167] Houston had suffered a serious wound to his pes during the battle[168] and on May 28 boarded the schooner Flora for medical treatment in New Orleans.[169]

Not until news of the victory at San Jacinto spread did the refugees return to their homesteads and businesses, or any was left subsequently the destruction acquired by both armies.[38] Throughout Texas, possessions had been abased and later on looted. Businesses, homes and farms were wiped out by the devastation of war. Ofttimes there was aught left to go back to, but those who went domicile began to pick up their lives and move forwards. San Felipe de Austin never really recovered from its total destruction. The few people who returned there moved elsewhere, sooner or later. Secretary of State of war Rusk later commended the women of Texas who held their families together during the flight, while their men volunteered to fight: "The men of Texas deserve much credit, but more was due the women. Armed men facing a foe could not merely be brave; but the women, with their lilliputian children effectually them, without means of defense or ability to resist, faced danger and expiry with unflinching courage."[155]

Run across besides [edit]

- Timeline of the Texas Revolution

Notes [edit]

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ a b In 19th century Mexico, Federalism was the empowerment of local governments, while Centralism sought to eliminate local political ability and requite information technology all to the national government.[1]

- ^ 193,600 square miles (501,000 km2), Mexican provinces of Coahuila and Texas.[2]

- ^ The Conditional Army of Texas consisted of three different categories of enlistees. The Army was much like a modern-twenty-four hour period army in its command structure, and had a two-year enlistment period. Permanent Volunteers ran a democratic structure allowing internal elections, and was for the elapsing of the war. The Volunteer Auxiliary was short-termed with an enlistment period of only six months.[14]

- ^ a b Locally organized volunteer militias were initially split from the Provisional Regular army of Texas and operated autonomously. Whether or not they were paid, or had supplies or uniforms, varied. Each had its own framework and elected leaders. They decided as a unit of measurement which battles they would fight. The Consultation but made Houston commander-in-chief of the paid provisional army he was to recruit and train. On March iv, 1836 at Washington-on-the-Brazos, the Convention as well put the volunteer militias nether Houston'south command.[15]

- ^ While it is not certain what became of the cannon, Santa Anna ordered all brass and bronze arms seized later on the battle to be melted downward.[27]

- ^ Historians disagree equally to the clarity of Houston's orders. In a alphabetic character dated January 17, 1836, Houston's wording seems to leave the terminal conclusion to provisional Governor Henry Smith. "Colonel Bowie will exit here in a few hours for Bexar, with a detachment of from xxx to fifty men. I have ordered the fortifications in the boondocks of Bexar to be demolished, and if you recollect well of it, I will remove all the cannon and other munitions of state of war to Gonzales and Copano, accident upward the Alamo, and abandon the place, as it will be impossible to keep upwards the Station with volunteers." The fractious conditional government had impeached Smith on January 11.[44]

- ^ a b A historical plaque denotes the Sam Houston Oak in front end of the Braches Business firm, which itself is on the NRHP.[73]

- ^ The ferry and trading post had been built by Jesse Burnam in 1824, and had survived numerous attacks from Karankawa indians. Burnam later claimed Houston destroyed his property because of personal bug betwixt the two, non because of whatsoever threat from the Mexican army.[83]

- ^ Historians Jack Jackson and John Wheat in their research of Mexican regime records believe that although the wording of the December xxx, 1835 Tornel Prescript specified "foreigners", the document was a mere formality to light-green-light Santa Anna's broader plan of dealing with opposition both foreign and domestic. In a letter of the alphabet to General Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma on February 29, 1836, Santa Anna wrote "in this state of war there are no prisoners". At the Battle of the Alamo, prior to the terminal siege, he offered a three-twenty-four hour period amnesty to allow Tejanos inside the mission to leave unharmed. At other skirmishes in the war, there is no indication either he or his generals fabricated that distinction. Jackson and White stated, "When he learned that Urrea had taken several hundred prisoners nigh Goliad, Santa Anna expressed his anaesthesia that they had not been treated as pirates and swiftly executed equally Tornel's decree specified. He sent more messages until the tragic act was done."[98]

- ^ a b Chaser General David Thomas was named as acting Secretary of War when Rusk joined the army.[117]

- ^ In Texas history and in historical works on Sam Houston, this is referred to every bit "the fork in the road" where Houston stopped retreating and instead actively pursued Santa Anna. The site is now designated as a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark and located in the present 24-hour interval Harris County city of Tomball.[146]

- ^ The terminal fate of the Twin Sisters cannons is unknown. Afterwards the Battle of San Jacinto, the cannons were sent to Austin, Texas, to be used for formalism purposes. When the cannons were discovered to be in New Orleans, Sam Houston petitioned for their return to Texas at the onset of the Civil War. Their last known whereabouts was in 1863 at the Battle of Galveston. Replicas are on display at the San Jacinto Battlefield State Historic Site.[165]

- ^ Houston'south agreement when he impressed the Yellowstone steamboat Apr 2 through April 14, was for Ross and the 17-man coiffure to receive at least one/3 of a league of country (more for officers) as payment. The crew was not obligated to fight. When Stephen F. Austin died in December 1836, the Yellowstone transported his body to Brazoria Canton for burying. Nil is known about the steamer after 1837.[166]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), pp. two, four, 6.

- ^ Tucker (2012), pp. 151–152.

- ^ McKay, Southward. Due south. (2010-06-12). "Constitution of Coahuila y Tejas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Clan. Retrieved December 1, 2014. ; Haley (2002), p. 116.

- ^ Davis (2004), p. 143; Todish et al. (1998), p. 121.

- ^ Davis (2004), p. 200.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 125.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 34.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 23.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 24.

- ^ Steen, Ralph W. (2010-06-15). "Full general Quango". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Clan. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014.

- ^ Steen, Ralph W. (2010-06-15). "Henry Smith". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Association. Retrieved December ane, 2014.

- ^ Haley (2002), p. 116.

- ^ Lack (1992), p. 76.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), pp. xiv–xv, 24; "Announcement of San Houston, A Call for Volunteers, December 12, 1835". Texas Land Library and Athenaeum Commission. State of Texas. Retrieved December ane, 2014.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), pp. fourteen, 44, 46, 75, 127.

- ^ Kelso, Helen Burleson (2010-08-31). "Edward Burleson". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December one, 2014.

- ^ Muir, Andrew Forest (2010-06-15). "Harrisburg, Texas (Harris County)". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Clan. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Todish et al. (1998), p.126; Steen, Ralph Westward. (2010-06-fifteen). "Conditional Government". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Country Historical Association. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 161.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 161; Lack (1992), p. 83.

- ^ Hatch (1999), p. 188; "The Texas Revolution: Role C (Jan–March 7, 1836)". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Association. 2010-05-20. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Advertising interim authorities". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. 2010-06-09. Retrieved September xvi, 2015.

- ^ Lack (1992), p. 77.

- ^ a b Lindley, Thomas Ricks (2010-06-xv). "Gonzales Come and Take It Cannon". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Clan. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Hardin, Stephen L. (2010-06-fifteen). "James Clinton Neill". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Country Historical Association. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Hardin, Stephen L. (2010-06-15). "Battle of Gonzales". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved Dec ane, 2014.

- ^ Davis (2004), p. 223.

- ^ Davis (2004), pp. 142–145.

- ^ Davis (2004), p. 147.

- ^ a b Todish et al. (1998), p. 124.

- ^ Guthrie, Keith (2010-06-15). "Battle of Lipantitlán". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December ane, 2014.

- ^ Davis (2004), pp. 157–159; Barr, Alwyn (2010-06-12). "Battle of Concepcion". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Country Historical Association. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014.

- ^ Barr, Alwyn (2010-06-15). "Grass Fight". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Clan. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Denham, James K. (January 1994). "New Orleans, Maritime Commerce, and the Texas War for Independence, 1836". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Texas State Historical Association. 97 (3): 510–534. JSTOR 30241429. ; "The Siege of Béxar". Texas Library and Athenaeum Commission. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ Davis (2004), pp. 182–185.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 29, 125.

- ^ Davis (2004), pp. 75, 186–187; Roell, Craig H. (2010-06-fifteen). "Matamoros Expedition". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Association. Retrieved December i, 2014.

- ^ a b c Covington, Carolyn Callaway (2010-06-15). "Delinquent Scrape". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 1, 2014. ; Moore (2004), pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Todish et al. (1998), pp. 126–127.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 128; Jackson, Wheat (2005), p. 372.

- ^ Bishop, Curtis (2010-06-09). "Battle of Agua Dulce Creek". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Association. Retrieved December one, 2014. ; Hartmann, Clinton P. (2010-06-12). "James Walker Fannin Jr". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Clan. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), pp. 29, 125.

- ^ Reid, Jan (May 1989). "The Runaway Scrape". Texas Monthly. p. 130. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), pp. 31, 139, 226; Hardin, Stephen L. (2010-06-09). "Battle of the Alamo". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Country Historical Association. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ McDonald, Archie P. (2010-06-15). "William Barret Travis". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Association. Retrieved December ane, 2014.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p.126; Moore (2004), p. 39.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 43; Moore (2004), p. 28.

- ^ Poyo (1996), p. 53, 58 "Efficient in the Crusade" (Stephen 50. Harden); Lindley (2003), p. 94, 134.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 142.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 22–24, 51.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 49, 51.

- ^ Beazley, Julia (2010-06-15). "Sidney Sherman". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Clan. Retrieved December one, 2014. ; Moore (2004), pp. 24–27, 51.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 28.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 28–29, 51.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 39–twoscore.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 39–43, 46, 51.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 45–46, 163, 171.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 47, 67.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. nineteen–22, 51.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 48.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 51.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 56.

- ^ a b Hardin, McBride (2001), p. ix.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 179.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 57–threescore; Hardin, McBride (2001), p. 9.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 60.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 58.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 59.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 61–63.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 63–67; "Sam Houston Oak". Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks. Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved December i, 2014. ; "Braches Firm". NRHP Texas landmarks. Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved December ane, 2014.

- ^ Davis (2004), p. 241.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 77–79.

- ^ Muir, Andrew Forest (2010-06-15). "Jane Birdsall Harris". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014. ; Todish et al. (1998), p. 103; Moore (2004), p. 139.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 129.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 68

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 71–72.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 66; "Site of the Camp of the Texas Army". Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks. Texas Historical Committee. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 69–73.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 75–76, 83; "Route of the Texas Army". Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks. Texas Historical Committee. Retrieved December i, 2014.

- ^ Watts (2008), p. 18; Awbrey, Dooley (2005), p. 537; Haley (2002). pp. 126–127; "Burnam's Ferry". Texas Historical Committee. Retrieved Dec 18, 2014. ; Largent, F. B. Jr. (2010-06-12). "Burnam's Ferry". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December nineteen, 2014. ; Largent, F. B. Jr. (2010-06-12). "Jesse Burnam". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Country Historical Association. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ Allon Hinton, Don Allon (2010-06-12). "Columbus, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 90, 94–95.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. ninety, 97, 99–103, 118–120, 126.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 94, 95.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 107, 111.

- ^ Roell, Craig H. (2010-06-12). "Boxing of Coleto". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Association. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014. ; Todish et al. (1998), p.130.

- ^ a b Moore (2004), p. 147.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 114, 144, 171.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 100

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 126–130.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 114–118.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 117–118.

- ^ Haley (2002), p. 129.

- ^ Jackson, Wheat (2005), pp. 374, 377, 386–387; Poyo (1996), pp. 53, 58 "Efficient in the Cause" (Stephen L. Harden); Lindley (2003), pp. 94, 134; Todish et al. (1998), pp. 137–138.

- ^ Haley (2002), p. 130.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 128–133.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 128.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 135–136.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 136–137.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 145–146, 163–164.

- ^ a b Christopher, Charles (2010-06-15). "San Felipe de Austin de Austin, Tx". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 140–141.

- ^ Berlet, Sarah Groce (2010-06-15). "Groce's Ferry". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Association. Retrieved December i, 2014.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 162.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 151–152.

- ^ Cutrer, Thomas W. (2010-06-15). "Edwin Morehouse". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Country Historical Association. Retrieved December ane, 2014. ; Moore (2004), p. 157.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp.147–148.

- ^ a b Moore (2004), p. 149.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 157–158.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 194–195.

- ^ Benham, Priscilla Myers (2010-06-15). "Thomas Jefferson Rusk". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Country Historical Association. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014. ; Moore (2004), pp. 165, 167,169.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 189.

- ^ Kemp, 50. W. (2010-06-15). "David Thomas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 1, 2014. ; Moore (2004), pp. 183–185.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 156.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 176.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 179,181.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 182.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 186.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 186–187.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 198–200.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 203–204; Gambrell, Herbert (2010-06-15). "Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Land Historical Clan. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Greene (1998), pp. 19–21.

- ^ "John V. Morton". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. 2010-06-15. Retrieved December i, 2014.

- ^ Hardin, Stephen F. (2010-06-15). "Thompson'southward Ferry". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Moore (2004), pp. 206–207.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 212.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 207.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 195–197, 207.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 219–220; Fischer (1976), p. 88.

- ^ Davis (2004), pp. 264–165.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 218–219, 232–233; Todish et al. (1998), p.130.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 15, 152–153.

- ^ Hunt, Jeffrey William (2010-06-15). "Twin Sisters". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 185; Haley (2002), p. 137.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 171–173, 201–202.

- ^ a b Moore (2004), pp. 212–213.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 214; "Charles Donoho Plantation". Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks. Texas Historical Committee. Retrieved December one, 2014.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 215–217.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 211–212.

- ^ "Samuel McCarley Homesite". Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks. Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved December 1, 2014. ; Moore (2004), pp. 220–221.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 222.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 225; "Abraham Roberts Homesite". Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks. Texas Historical Committee. Retrieved Dec 1, 2014.

- ^ "Robbins'south Ferry". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Clan. 2010-06-15. Retrieved December 1, 2014. ; Moore (2004), pp. 226–227.

- ^ "Matthew Burnett Homesite". Recorded Texas Celebrated Landmarks. Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved December 1, 2014. ; Moore (2004), p. 229.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 227–228.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 233–235, 243.

- ^ MOORE, KAREN (June 15, 2010). "Isle of man, PAMELIA DICKINSON". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved Baronial 8, 2019.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 230–232.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 230; "Lynchburg Boondocks Ferry". Recorded Texas Historical Landmarks. Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 235–237.

- ^ a b Downs, Fane (1986–1987). ""Tryels and Trubbles":Women in Early Nineteenth-Century Texas". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association. 90: 50–55.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 242, 295–296; "Sam Houston Crossed Buffalo Bayou". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Country Historical Clan. Retrieved December 1, 2014. ; Moore (2004), p. 251.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 246.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 264, 267.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 295.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 298; Todish et al. (1998), p. 131.

- ^ a b Moore (2004), p. 230.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 328–329.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 337,353,377.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 344–345.

- ^ "San Jacinto and the Mystery of the Twin Sisters Cannons". Texas State Cemetery. State of Texas. Retrieved Dec one, 2014. ; Moore (2004), pp. 333–336.

- ^ Burkhalter, Lois Wood (2010-06-xv). "Yellow Stone". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December i, 2014. ; Greene (1998), pp. 19–21.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 375–386,405–407.

- ^ Moore (2004), pp. 338–339.

- ^ Moore (2004), p. 407.

References [edit]

- Awbrey, Betty Dooley; Dooley, Claude (2005). Why Stop?: A Guide to Texas Historical Roadside Markers. Lanham, Dr.: Taylor Merchandise Publishing. ISBN978-i-58979-243-2.

- Davis, William C (2004). Lone Star Rising: The Revolutionary Birth of the Texas Republic . New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN978-0-684-86510-ii.

- Fischer, Ernest G. (1976). Robert Potter: Founder of the Texas Navy. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company. ISBN978-ane-58980-473-9.

- Greene, A. C. (1998). Sketches from the V States of Texas. College Station, Texas: Texas A & Grand University Press. ISBN978-0-89096-842-0.

- Haley, James 50. (2002). Sam Houston . Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN978-0-8061-3644-8.

- Hardin, Stephen L. (1994). Texian Iliad-A Military History of the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: Academy of Texas Press. ISBN978-0-292-73086-1.

- Hardin, Stephen; McBride, Angus (2001). The Alamo 1836: Santa Anna'due south Texas Campaign. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-one-84176-090-2.

- Hatch, Thom (1999). Encyclopedia of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN978-0-7864-0593-0.

- Jackson, Jack; Wheat, John (2005). Almonte's Texas: Juan N. Almonte'due south 1834 Inspection, Hole-and-corner Report & Office in the 1836 Campaign. Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association. ISBN978-0-87611-207-half dozen.

- Lack, Paul D. (1992). The Texas Revolutionary Feel: A Political and Social History 1835–1836. College Station, Texas: Texas A & Thou University Printing. ISBN978-0-89096-497-two.

- Lindley, Thomas Ricks (2003). Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions. Plano, Texas: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN978-one-55622-983-1.

- Moore, Stephen Fifty. (2004). Eighteen Minutes: The Battle of San Jacinto and the Texas Independence Entrada . Plano, Texas: Commonwealth of Texas Press. ISBN978-ane-58907-009-7.

- Poyo, Gerald Eugene (1996). Tejano Journey, 1770–1850. Austin, Texas: Academy of Texas Press. ISBN978-0-292-76570-ii.

- Todish, Timothy J.; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1998). Alamo Sourcebook, 1836: A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution. Austin, Texas: Eakin Printing. ISBN978-1-57168-152-ii.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2012). The Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War [3 volumes]: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-1-85109-853-8.

- Watts, Marie W. (2008). La Grange (Images of America: Texas). Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN978-0-7385-5636-9.

Further reading [edit]

- Winders, Richard Bruce (Apr 4, 2017). ""This Is A Brutal Truth, But I Cannot Omit It": The Origin and Outcome of Mexico'south No Quarter Policy in the Texas Revolution". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 120 (4): 412–439. doi:10.1353/swh.2017.0000. ISSN 1558-9560. S2CID 151940992.

External links [edit]

- Sonofthesouth.net: The Runaway Scrape

What Was The Runaway Scrape,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runaway_Scrape

Posted by: dupreanducce.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Was The Runaway Scrape"

Post a Comment